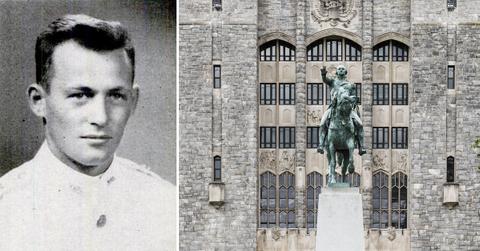

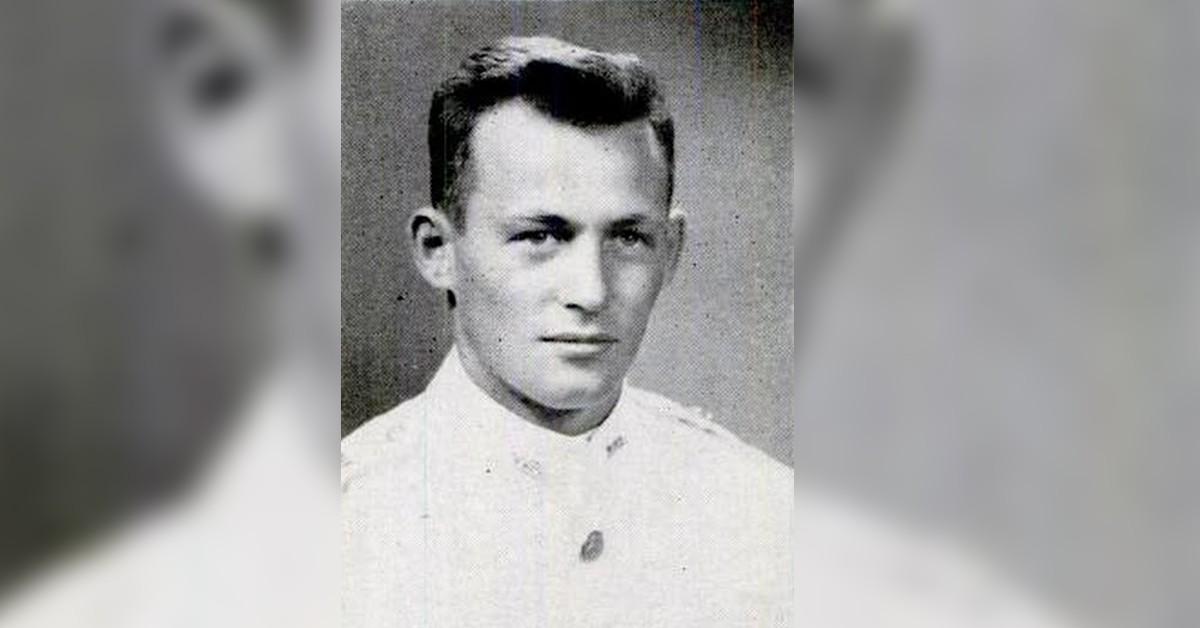

He was a cadet at West Point military academy, but vanished without a clue. What happened to Richard Cox?

Oct. 2 2021, Published 12:45 p.m. ET

When people vanish, there is almost always some trace left behind that leads investigators to discover their location, dead or alive.

Perhaps background checks will reveal somewhere they might flee, or inquiries will reveal enemies, debts or threats against their life. However, rarely will somebody vanish without any clue where they're going or what might have happened to them. It's almost as if they simply walked away and disappeared into thin air. Such is the case of West Point cadet Richard Colvin Cox.

Born in Mansfield, Ohio, on July 25, 1928, Richard "Dick" Colvin Cox came from a middle-class and religiously conservative family. Cox's father, Rupert, believed solely in the power of prayer as a lost element of healing, refusing treatment for a diabetic condition that eventually killed him when Richard was 10.

Losing his father meant that the young Richard and his five siblings had to work extra for the household, the young man having little time for athletic pursuits in high school. He already worked a part-time job that extended to full time in the summer. On one occasion, when Cox severely cut his arm during work as part of a road crew, his mother, Minnie, again refused to call a doctor. The wound became infected, and eventually, neighbors were forced to intercede to take him to a medical facility.

Cox graduated high school in 1946, a time of profound change for both the world and the United States. The Second World War was newly won, and the new threat faced by Washington was the Soviet Union. The military had whole new responsibilities as the era of the red scare got underway, including perhaps most importantly, the occupation and relief of West Germany. Into the atmosphere stepped Cox, enlisting in the United States Constabulary, a police-type force designed to provide security in the occupied West German zones.

By 1947, Cox was stationed in Coburg, Germany, a town located by the Itz river in Bavaria, and was in the S-2 section at headquarters, dealing in intelligence. Later that same year, he applied to West Point and arrived at the United States Military Academy in January 1948, beginning his training in May. While he wasn't amongst the top rank in the class, he wasn't far off and certainly seemed to have a bright future personally and in his career. At the time, he was engaged to be married to Betty Timmons.

STRANGERS IN STRANGE MEETINGS

Around 4:45 p.m., Jan. 7, 1950, Peter Hains received a phone call. Hains was a classmate of Cox at West Point and was Charge of Quarters in Cadet Company B-2, the individual tasked with guarding the entrance to North Barracks. He also answered incoming calls of members of the company. Hains told the caller that Cox was in his room and, as later recanted, his tone became "rough and patronizing, almost insulting."

"Well, look, when he comes in, tell him to come on down here to the hotel. ... Just tell him George called – he'll know who I am," the man told Hains. Adding, "We knew each other in Germany. I'm just up here for a little while and tell him I'd like to get him a bite to eat."

Hains could not be sure the man had called himself "George" as he quickly dismissed the call from his mind as merely one of the hundreds of inquiries made each week. Interestingly, throughout the rest of the story, Cox would never refer to the man by any name during conversations with friends, calling him only "that man" and "my friend."

Just under an hour later, around 5:30pm, a man entered Grant Hall, an area set aside for guests to meet cadets and asked to see Cox. The cadet on duty, Cadet Officer of the Guard Mauro Maresca, informed Cox and the two men greeted each other warmly with Cox exclaiming that the man was "the last person I expected to see" and the visitor joking about how Cox looked in his uniform.

Cox signed out on the departure book and indicated he would be having dinner off-campus. The man was described as fair-haired and with a fair complexion by Maresca. He wore a trench-coat, but no hat. There would be no indication if this was the same man who had been on the telephone, but it seems certain. Intriguingly a second description of the man later published in the press described him as "dark-haired and rough looking." It is unclear who gave this description.

Cox returned to his company later that evening, took a shower, and slept off the effects of the evening. As a prank, his two roommates photographed him slumped over his desk in a drunken stupor. At some point during the night, Cox awoke and ran from his room into the hall, shouting something that witnesses described as sounding like "Alice." His roommate Deane Welch asked what he meant, but Cox quietly returned to his bed.

In the coming months, Welch and another friend, Cadet Joseph Urschel, would say they believed "Alice" may have been a sweetheart that Cox had back in Germany whose photo he carried around in his wallet. They couldn't be sure whether Cox told them this or it was something they believed personally.

Since 1947, Cox had been engaged to Timmons, and it seems unlikely he would have carried another woman's photo with him. However, a letter to Germany would be returned a few weeks later that he had been addressed to a young woman. The address was unknown, and Cox simply wished to converse with her, not being sure if she remembered him. Whether this was "Alice" is unknown, and it had been written before the arrival of "George.".

At some point in the night, either Cox or somebody else changed the time he'd left barracks to 18:23 military time instead of the original 19:23, trying to make it look like he'd attended the cadet supper formation he'd skipped to meet with his friend. Missing the supper could have landed the gadget on a charge. Whether Cox woke up a second time or not is also unknown.

The following day before the usual Sunday chapel service, Cox spoke to his friends about the man he'd met, saying they had spent the evening in his friend's car drinking whisky and reminiscing over old times. According to Cox, the man was a former Army Ranger who he'd known in Germany who told plenty of stories about killing Germans. These stories including gruesome tales about severing their genitals and another about murdering a girl he'd got pregnant by hanging her.

Cox met with the man a second time that afternoon and returned around 4:30 p.m. despite having intended to return around two hours earlier. Cox made it plain ] he viewed the man's claims of committing war atrocities to be distasteful, and he was angry that his free time was being taken up with the man, telling his friends that he "hoped he wouldn't have to see the fellow again."

The following weekend on Jan. 14, Cox watched the basketball game between the Army and Rutgers from the USMA Fieldhouse at West Point, where the Army team won 58-54. Following the game, Cox was seen talking with another man whose description differed significantly from the supposed veteran.

The chapel at West Point

This man was said to be dark-haired and rough-looking by Cadet John Samotis. This tallies with the second description of the individual who arrived at the barracks. Still, it seems possible that the press merely became confused with two different accounts of his appearance, and the dim light of the area accounts for the discrepancy.

That evening Cox told his roommate he was indeed headed out to meet again at the Thayer Hotel, named in honor of "the Father of West Point" Brigadier General Sylvanus Thayer. He made it clear that the man he'd met after the basketball game was indeed "George."

Cox's manner was described by some as far from happy, seemingly disgusted at the prospect of meeting the mystery man once more. Welch, however, said that just before leaving, he hadn't seemed depressed or worried; instead, he was "lackadaisical."

Welch would be the last confirmed person to see his friend alive, with Richard Colvin Cox never seen again. Neither he nor "George" seemingly arrived at the Thayer, with nobody there remembering them entering or dining.

WITHOUT A TRACE

Cox didn't return by 11 p.m. as intended, but the alarm wasn't raised, with personnel failing to return not being uncommon. By 2:30 a.m., his absence was mentioned to his superior officer. Still, he was presumed to simply have been unable to return from a night of potential drinking, risking punishment for doing so. However, the disappearance was reported to the State Police, the Army Criminal Investigation Command and the FBI the following morning.

The entire grounds of West Point were thoroughly searched, with troops and a helicopter utilized in the effort. Every warehouse, shed, cellar, and attic was searched. The Lusk Reservoir, located right next to Michie Stadium at the academy, was dragged, the banks of the Hudson River were searched, and a nearby pond was even drained. A public appeal for information on Cox's whereabouts was broadcast locally, but nothing was found after two months of relentless searching.

Investigators could find no evidence that "George," the man he had been meeting, had ever existed in the form Cox claimed to friends. They searched records of every soldier he had served with in Germany, and all those of interest could not have been in West Point at that time. Cox was declared AWOL on March 15, 1950, and declared legally dead in 1957.

Investigators at West Point believed that harm had come to Cox, noting that he'd left behind $87 in his room, which amounts to more than $1,000 in today's money, and two suits of clothing. When he left, he had been attired in his uniform and gray cape overcoat, meaning that he would have found it difficult not to be spotted amongst a civilian population.

The presence of the civilian garments was not regular. Civilian clothing was usually stored in the basement, but Cox's had only just been returned from the cleaners after his Christmas vacation home. With the gear in his room, it seems evident that if he'd intended to go AWOL, he would have worn something other than his uniform.

Interestingly, the date Jan. 15 was circled on his desk calendar, the day after his disappearance. One friend said it was merely a reminder to buy basketball tickets, while his roommates denied this.

It would have been easy for Cox to leave as a passenger or prisoner in a car as sentries did not stop outgoing vehicles or inspect any identification. If he had been murdered, it would have been equally easy to drive him away. However, carrying out a killing on a military post would have been risky in the extreme, and Cox was said to have been in excellent physical condition, making any altercation not only tricky but likely to be discovered.

U.S. Army cadets today

Indeed, later evidence suggests that the assumption that Cox had been murdered was likely false, with eyewitnesses coming forward to say they had seen Cox alive sometime after his disappearance. There were dozens at the time, all of which were debunked, including a man in Korea. However, if true, this seems likely to have been a spur-of-the-moment decision considering that he left his possessions behind.

In 1982, Jim Underwood of the Mansfield News Journal wrote a 12-part series on the disappearance of Cox at high expense, looking to finally bring a resolution to the case. Underwood interviewed Ralph E. Johns, who had attended high school with Cox. By now, Johns was a juvenile and domestic relations judge and had a fascinating tale to tell.

Johns has been interested in the case ever since the 1950s, and at the time, he and his colleague William McKee had extensive links with the FBI. What they learned was far from the official story that said Cox was likely dead. Speaking with former FBI agent Vince Napoli, the agent told Johns the Bureau had been within 24 hours of apprehending Cox before they were pulled off the case.

In 1969, he requested files on the case under a Freedom of Information Act request. Excuses were made, and the files never emerged. Five years later and now a prosecutor, McKee sent an assistant up to the FBI office to ask for the files directly. Described as calm and collected before, the agent in charge was said to have gone white as a sheet. Still, the files were not produced. Intrigued as to why the FBI should be protecting a suspected deserter, Johns speculated that Cox had been moved into intelligence work, perhaps with the CIA.

The Mansfield News Journal was finally able to get the files in 1982, and they were heavily redacted with black lines censoring vast swathes of information. An astonishing 165 pages were missing. What could be so sensitive about a single and seemingly unremarkable missing cadet from West Point?

While the CIA theory excites a sense of adventure, does it really ring true that a man who wasn't even top of his class would be selected? How would he have come to the intelligence community's attention, and would he really have been asked to simply vanish into the night and draw so much attention? Spies are not much use when their image is plastered all over the newspapers, after all.

In 1985, retired high school teacher Marshall Jacobs looked into the case and become more intrigued the more he looked into it. He crossed the country, followed up old leads, and found plenty of new information. He was relentless in pursuing the truth, interviewing military friends, his classmates, CIA, FBI and CID agents, army officials and more. He scoured the archives at West Point and the FBI and came to conclude that Cox was not dead, having been helped into a new life by the mysterious "George."

While Jacobs was still conducting his investigation, including a new interview with Johns, FOX's "A Current Affair" broadcast a segment on the enduring mystery. Anchored by Krista Bradford, the piece featured an interview with Jacobs and a retired Coast Guard officer by the name of Ernest J. Shotwell Jr.

Shotwell Jr.'s testimony would be the best evidence yet that Cox was not dead. The retired officer stated two years after Cox apparently disappeared, he had met him at a Greyhound bus station in Washington D.C. The two were classmates at the USMA Preparatory School at Stewart Field, and at the time of their 1952 meeting, Shotwell had no idea that Cox was a missing person. Cox was said to be uncomfortable and vague about his future.

In 1996, Jacobs contacted Harry J. Maihafer for assistance on his book. Mahavir is a retired army colonel and banker who served in Korea, later forging a career in writing. With Jacobs' research and Maihafer's writing ability, together the two published "Oblivion," detailing the entire investigation while sadly failing to find a resolution to the mystery of what happened to Richard Colvin Cox — the Army cadet who vanished without a clue.

Become a Front Page Detective

Sign up to receive breaking

Front Page Detectives

news and exclusive investigations.