How a Killer Who Commandeered Teenagers and Targeted Girls Became Known as the 'Pied Piper of Tucson'

The story of Charles “Smitty” Schmid reads like a dark fairy tale, told by the best friend who ultimately turned him in to the cops. It’s the story of teenagers too loyal to their friend Smitty to do the right thing, and lawmen who dismissed the disappearance of three teen girls as runaways.

Most of all, it was a story loved by the media, who named the serial killer “The Pied Piper.”

Smitty was a charismatic non-conformist who was popular with girls admired by guys. It was rumored Schmid ran with mobsters and bragged about murder.

His best friend Richie Bruns agreed to help Smitty, 22, bury two bodies in the desert outside Tucson, Arizona, in 1964. Bruns decision led to the discovery of crimes that shocked Arizona and the nation.

Bruns hated himself for becoming a snitch and defying gangster code – a fate almost worse than death. He called the cops only because he worried his girlfriend might be Schmid’s next victim.

Bruns titled his autobiography detailing Schmid’s capture “I, a Squealer.”

He was the only teen who came forward, despite half a dozen of people knew Smitty was a killer.

‘THE PIED PIPER OF TUCSON’

The media gave Schmid the name “The Pied Piper of Tucson” because he seemed to command teenagers to follow him.

In 1960s Tucson, the last thing on anyone’s mind was murder. The city was a fast-growing paradise dotted with small, adobe homes and saguaro cactus. It was named “The Old Pueblo” because it was one of the longest inhabited settlements in the US.

Yet Tucson was new land full of promise – especially for families leaving behind oppressive winters in the Midwest. Within a decade, the place had grown from 50,000 to nearly 300,000 inhabitants. Schools burst at the seams, and teens sometimes attended classes in split shifts.

The straight, wide roads and unrivaled natural beauty also brought a few dangerous men. Mobsters moved west from New York or Jersey for the sunshine and safety. The rest of America barely knew Tucson existed, and its residents liked it that way.

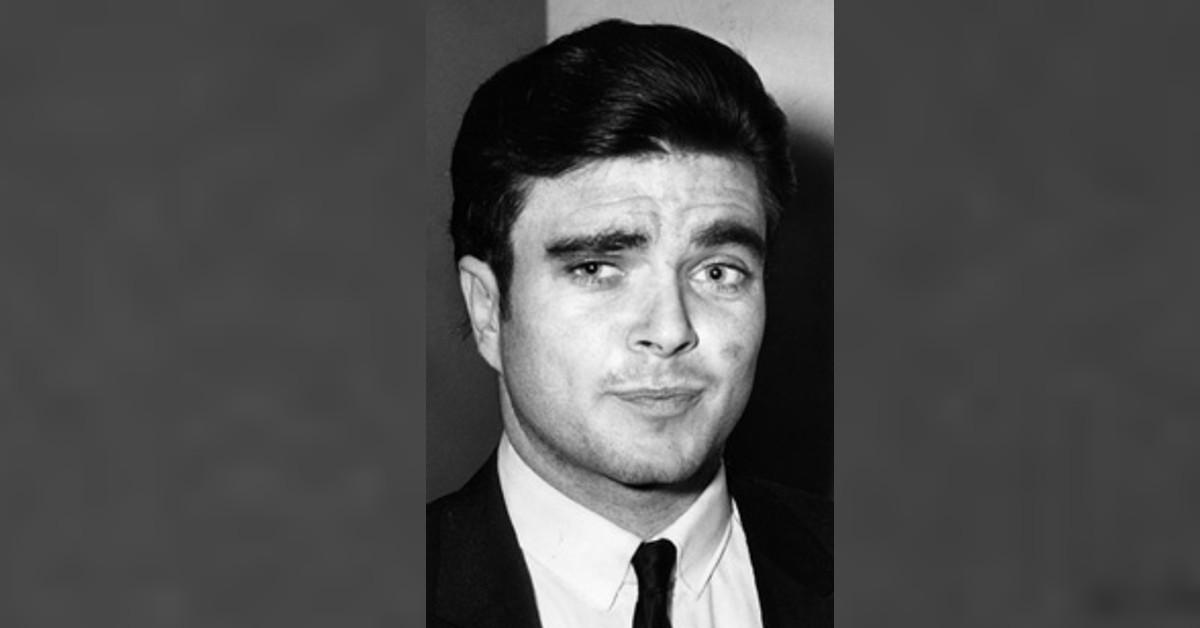

Schmid was born in Tucson on July 8, 1942, and given up for adoption the next day. He was what some would label a bully, but he grew into a handsome young man with plenty of friends and girlfriends willing to look past his intimidating demeanor. He tended to attract followers, believing they would keep their mouths shut. Smitty preferred hanging out with high school kids into his early 20s.

He was right about most of them – they never ratted on him and rarely questioned him – but he miscalculated when it came to Bruns.

RICHIE AND SMITTY

Schmid’s mother didn’t want a baby, and no one knows what became of his birth father. His adoptive parents, who ran a nursing home, were a hard-working couple who doted on their son.

In his late teens, Schmid claimed he tried to connect with his birth mother, who told him to get lost.

At only 5-feet-3-inches, Smitty was a stand-out athlete in school. Despite being an indifferent student, he was a naturally charming and intelligent kid who excelled as a high school gymnast.

The boy made it to the state gymnastic championship in 1960, according to the biography “Cold Blooded, the Saga of Charles Schmid.” With an athletic build and dark good looks, he attracted plenty of female attention. He had terrific manners and, in the slang of the 1960s wasn’t just interesting but neat.

Smitty would learn how to exploit his charisma.

He met Bruns, four years younger, in high school. Aside from his much geekier pal, John Saunders, Bruns would be Smitty’s closest friend.

Smitty once asked Bruns to buy him a pair of cowboy boots a few sizes too big. He didn’t want the store clerk to hassle him about boots two sizes too large. Bruns complied, and Schmid stuffed the boots with paper and crushed tin cans. He hobbled around for a while, but they proved too uncomfortable to use daily, according to Life Magazine.

He ended up giving the boots to Bruns.

In his senior year, Smitty quit the gymnastics team. The next year, he was ineligible due to being a fifth-year student but was suspended for stealing tools from the school welding shop, according to Life.

After leaving school, his adoptive parents continued to support him financially with a monthly allowance, a car, and a free place guest house on their property. He spent his money cruising the strip, taking dates out and bragging to his buddies Bruns and Saunders about his sexual conquests.

With his own place, he threw wild parties that only increased his popularity, according to Life.

LONE ALPHA WOLF

Schmid had several strange habits. With his ill-fitting boots, he had an awkward, halting gait. Some wondered if he was drunk, others didn’t what to make of the 22-year-old.

According to Life, his peers who had jobs and ambitions saw him as a creep. But the younger set, 14 to 18 years old, found much to admire.

He drew a black mole on his face, died his hair jet black and regularly used make-up. He is said to have stretched out his lower lip so he would look more like Elvis Presley. In short, Smitty was vain and narcissistic.

He spent his free time cruising the strip, the two-laned main drag in town, or pulling into the high school parking lot in a souped-up car. Adults questioned his odd habits or why he was hanging out with kids five years younger.

Schmid’s followers believed his tales of running with mobsters. But most importantly, they looked the other way when he told them he wanted to kill someone, just to know what it felt like.

Like another infamous murderin Milpitas, California in 1981 upon which the hit film “River’s Edge” was based, the teens remained quiet. Marcy Conrad, a 14-year-old dreamer, was murdered by a boy she barely knew from her high school, and her friends went to view her body – tossed down a ravine – but never told anyone. An acquaintance who heard the rumor that Conrad had been murdered came forward.

Schmid’s coterie was either too scared of him or too frightened of the personal consequences to come forward.

When law enforcement later discovered the scope of “the Pied Piper’s” crimes, they realized his friends and followers might have prevented some of the bloodshed by at least telling an adult.

“I WANT TO KILL A GIRL!”

On the night Alleen Rowe disappeared, May 31, 1964, Schmid was hyped up and talkative. He allegedly told his girlfriend Mary French and Saunders, “I want to kill a girl!” I want to do it tonight. I think I can get away with it!”

It was already hot in Tucson and final exams were underway. Rowe, a good student, had kissed her mom goodnight after studying for an exam the next day. Her mom, a nurse who worked nights, last saw her daughter settle off to sleep before she left for work.

Rowe was 15 years old and prone to dreaminess. She had recently made friends with a neighbor girl, Mary French. On this night, French showed up at her window, and Rowe left with her, Schmid and Saunders, even though she’d told her mother she thought Smitty was creepy, according to Life.

It seems that Schmid had targeted Rowe as a victim shortly after he met her.

He enlisted French and Saunders to help him in the crime. The three drove Rowe to a remote spot in the desert, where French told Rowe they could relax and drink beer.

Schmid raped Rowe before beating her to death with a rock, then Saunders and French helped dig a shallow grave. The trio wiped Schmid’s car completely clean of any trace of Rowe and left the scene together, swearing secrecy, according to Life.

When they were questioned about what happened to Rowe, Schmid and the two accomplices probably shrugged their shoulders and said, “Maybe she ran away?” At the time, Tucson police routinely assumed missing teens were runaways.

Charles Schmid

For almost a full year, Schmid stayed out of trouble in Tucson. Then, he chose his next two victims: a girl he’d been dating on the down-low named Gretchen Fritz, 17, and her younger sister.

He met up with Fritz and her sister Wendy, 13. This time, Schmid committed the murders by himself, but he would later need help to cover up the bodies, which he’d left in an obvious spot frequented by high school partiers.

Schmid got hold of his pal Bruns, who agreed to give him a hand.

THE DEATHS OF GRETCHEN AND WENDY FRITZ

Rowe’s mom was pleading with police to take her daughter’s disappearance seriously. She had little leverage as a single, middle-class mom. Gretchen and Wendy came from a prestigious family, however. Their dad was a well-known Tucson heart surgeon. He, too, would run into trouble tracking down his daughters.

The Fritz family was used to Gretchen’s difficult behavior. According to Life, a teacher once described Gretchen, a thin and nervous blond, as “a psychopathic liar.”

Gretchen was tied much more closely to Schmid – she was his girlfriend in 1965.

A was a natural blond (and Smitty loved blond girls), and she didn’t back down easily. The two fought nearly constantly, according to a later account by Bruns.

With Gretchen it was different. She wasn’t afraid of Smitty, and she knew his secrets. Richie Bruns later testified, “First, she would get suspicious of him. Then, he would get suspicious of her. They were made for each other.”

Smitty told Gretchen a few white lies, as he did with most women he dated, making up stories about being stricken with a terminal illness. He might have told Gretchen, too, that he was really adopted and his birth mother had coldly rejected him as a teen, even though his adoptive parents were lenient with him and tolerant of his wayward lifestyle.

He’d told Gretchen he murdered Rowe and buried her body in the desert. She said nothing, but she believed him.

Then Gretchen made a crucial mistake – she refused to let Smitty go. He wanted to break up; she didn’t. She threatened to tell the cops what she knew about Rowe. Smitty bided his time, then agreed: let’s should stay together.

A few nights later, on Aug. 16, 1965, the sisters left for a drive-in movie in Gretchen’s red car. Both disappeared into thin air. An investigation found the car parked behind a motel in town. Police told the Fritzes their daughters were runaways.

The police didn’t consider Schmid, who was tied to three murders, a suspect. A private detective, however, questioned Schmid a week after the two girls disappeared. He’d found a business card associated with Schmid in Gretchen’s car, which was abandoned a half-mile from Schmid’s house, according to Radford University.

THE MOB CONNECTION

Not long after the Fritz sisters went missing, Bruns was hanging out at Smitty’s house. His friend told him point-blank he killed both sisters. Bruns, according to “I, Squealer,” wasn’t sure whether to believe him. He’d never seen Rowe’s body – despite his friend’s insistence he killed her – and he hated Gretchen, anyway.

Bruns let it slide, until he got caught up in a scarier web.

One night, Smitty came to pick Bruns up in the company of several large, well-dressed men. They went to a home where several other men explained they’d been hired to find Gretchen and Wendy. They intimated they knew the two young men were involved.

Smitty later told Bruns he was sure they were Mafia.

Bruns knew something was up when he witnessed his friend phone the FBI for help. An agent said they would intervene. Bruns told Smitty, “Let’s bury the bodies,” and he meant it. His friend had told him during his confession that he left Gretchen and Wendy in the most obvious spot he could think of.

They buried the two, and Bruns was ready to move on with his life. He was dating a girl Smitty had tossed aside named Kathy, and recently he’d fallen head over heels in love.

Kathy, however, broke it off. That sent Bruns into a frenzy of love-letter writing. In his state of lovesick delirium, he began to imagine Smitty would target Kathy next. He wrote in “I, Squealer” that he began to have the same, horrifying nightmare every night.

Schmid was murdering her, over and over.

Bruns decided his only job now was to protect Kathy from this murderous fiend, so he virtually camped out on her front porch. Kathy’s family had had enough and called the cops. He was sent to jail, then exiled to Ohio to live with his grandmother.

In Ohio, he broke down one night and told his grandmother the whole story. She persuaded him to call the Tucson police. His testimony would put Schmid behind bars after the cops dug the bodies of Gretchen and Wendy out of the desert sand.

THE AFTERMATH

Bruns took the stand, the primary witness against Schmid as the trial got underway in January 1966. Several other teenagers also testified under oath, reluctantly admitting they knew what happened but never would have told, not wanting to “fink” on their friend.

Ultimately, according to Life, half a dozen teens probably knew Rowe, Gretchen, and Wendy were murdered.

The story ended not with a bang but a whimper. The trial dominated local headlines. Life, Playboy, and Time Magazine did in-depth pieces covering the 1966 trial. Life intimated Tucson was a dangerous backwater where teens ran wild, with kids roaring up and down the strip all summer, too bored for any other pastime, unable to find summer jobs.

Their photos of the strip made it look like a jumble of nothing more than fast-food hangouts and liquor stores.

Bruns published his story, in which he admitted he hated himself for being a disloyal friend.

In 1967, authorities finally found Rowe’s remains. Her mother, who’d been labeled a nuisance for never giving up the search, was vindicated but still torn apart by grief.

In 1972, Schmid escaped from prison after several failed attempts. He and a triple murderer named Richard Hudgens gained their freedom for a time but were recaptured after taking four hostages outside of Tempe, according to The New York Times.

Two-and-a-half years after his last failed attempt to flee, two inmates attacked Schmid, 32, with homemade shanks. They stabbed him in the head and chest nearly two dozen times, and he died in a prison hospital 10 days later, according to The Tucson Citizen.

His adoptive parents refused to claim the body, and Schmid was buried in a potter's field at the prison.

Become a Front Page Detective

Sign up to receive breaking

Front Page Detectives

news and exclusive investigations.