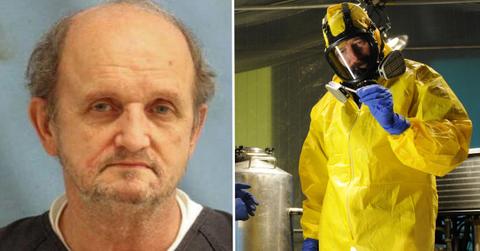

Real-Life Walter White: How an Arkansas Man Went from Respected Judge to Meth Head Behind Bars

In 2011, Travis Blaine Perkins of Pocahontas, Arkansas, was arrested for manufacturing and possessing methamphetamine. He was a likable guy with plenty of family in town and his own apartment, where he regularly hosted a friend or two for a game of darts and a few hits of meth.

Travis, 34, towered at 6-feet-6-inches, but he was a gentle giant. This wasn’t his first meth-related arrest.

Travis was found murdered in his bed, with two gunshots to the face, four days before he was set to turn state’s evidence against two co-defendants: Bob and Jerrod Castleman.

This is the story of one of those men, Bob Sam Castleman, a former district judge and an all-around good guy from small-town Arkansas. A story told through interviews, media reports, legal filings and books about how he went from that to notorious killer.

IN THE FOOTHILLS OF THE OZARKS

Randolph County is the oldest established county in Arkansas. It’s been populated by white settlers since the time the Declaration of Independence was signed. Before that, it was rich hunting grounds for Shawnee and Cherokee tribes. Locals still find arrowheads and other artifacts in the fields and dense woods.

The post office in the county seat of Pocahontas still stands, as does the town courthouse, but an outlaw ethos has never left part of the country. Plenty of locals ran moonshine, and Public Enemy #1, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis once drove up from the gambling mecca of Hot Springs to hide out from the feds in Pocahontas.

Moonshine doesn’t make the news these days, but meth does. Arkansas has the worst meth problem in all fifty states, with more than 1 in 4 adults in the state testing positive for the drug in 2020. The next closest, Iowa, had a 20.8 percent rate.

In most rural counties in northern Arkansas and southern Missouri, meth labs dot the region, secreted away in mobile homes, apartments and vehicles. Local law enforcement can’t keep up.

Driving west, Pocahontas lies at the end of the flat Mississippi delta, just before the land rises into the Ozark Mountains that stretch across northern Arkansas, southern Missouri, and northeastern Oklahoma. It’s where Bob Castleman purchased a 262-acre farm after he retired from his career as a municipal judge.

He retired to spend more time on the farm with his son, Jerrod Castleman.

During his tenure on the bench, Bob Castleman put plenty of meth cooks and dealers away. But the drugs, like the creeping vines that climb up the Arkansas hardwoods, would slowly worm their way into his comfortable, respectable life.

In 2015, a summary of the case detailed their drug histories:

“Bob Sam Castleman was charged with conspiracy to manufacture methamphetamine, maintaining drug premises, and conspiracy to possess chemicals and equipment used to make methamphetamine. Some evidence supporting these charges came from a traffic stop in Walnut Ridge, Arkansas and a later search of open fields on Castleman's property.”

SNAKES IN A PICKUP

Bob had his first tangle with local law enforcement in January 2004, when he and Jerrod pleaded guilty to mailing a live copperhead snake to their neighbor, Albert Coy Staton. It was an open and shut case in more ways than one, as Staton’s wife opened a peculiar-looking box one day as she was pulling into her driveway. Amidst the Styrofoam peanuts, a viper’s head emerged, wriggling toward her face.

She reacted out of instinct, tossing the snake-filled box onto the lap of another passenger. He, in turn, threw it out the window. The box landed top-down, trapping the reptile.

When the cops showed up, it wasn’t hard to see the evidence: a 28-inch-long copperhead that had been sliced in two, fangs intact. The bisected serpent was put down by a lawman with a single shot.

Because the snake was delivered through the mail, the crime brought federal charges. Bob and Jerrod were found guilty based on fingerprints found on the package and sentenced to several years in federal prison. Due to a prior conviction, Jerrod received a harsher sentence.

Staton purchased an ATV from Jerrod Castleman not long before the snake incident. He told the Castleman’s the vehicle needed repairs, which ignited a feud between the neighbors.

At the time of his first arrest, Bob Castleman tested positive for drugs. He’d only been retired for a few years.

THE POCAHONTAS METH CONSPIRACY

On a mild Spring day in April 2011, a cop pulled the Pocahontas' retired judge over as he was driving in a nearby town.

Bob Castleman, 63, and his 30-year-old girlfriend, Becky Spray, made purchases that raised the suspicions of an employee of the Farm Services store in Walnut Springs.

Seeing Becky purchase vinyl tubing—a well-known tool for meth cooking—the shop clerk called police in nearby Hoxie because he knew they were fast out the door. It was a cop from Hoxie who stopped Bob and Becky as they drove out of Walnut Springs.

Officers search the truck and found supplies used to cook meth, including a can of Coleman fuel, four boxes of pseudoephedrine pills, tubing and a box of plastic bags.

Bob Castleman and Becky were arrested.

Bob’s farm was now on law enforcement radar, and the cops descended on it the next day. They found Jerrod, along with some pot. When they hiked up the hill behind the house, they uncovered meth-related supplies and meth residue in a trailer. Jerrod went on record shortly after he was arrested. Who brought the supplies? Who sold the meth? Who cooked for him?

Jerrod wasted no time in identifying his friend Perkins.

HOW BOB CASTLEMAN GOT INTO THE METH BIZ

In court, Castleman’s lawyer argued that Bob Castleman did no more than make his sprawling farm available so his son Jerrod could cook meth.

Jerrod testified under oath his father got into the meth-cooking business this way: one day, Bob Castleman told his son he thought he’d been “ripped off” and been sold “bad stuff.” Jerrod “hinted that [he] might be able to fix the problem.” Jerrod knew his friend, Perkins, “was cooking meth at the time and he sometimes needed a place to go.”

Perkins and Jerrod began manufacturing meth on Bob Castleman’s property because his father “basically told me he didn't want to know nothing about it.”

The deal was, Jerrod and Perkins would get pseudoephedrine pills from any visitors, then use them to cook on the farm. They routinely carried the cooked methamphetamine on a coffee filter into the house to dry and would later smoke some with any visitors on hand. Bob Castleman was sometimes around when they brought the coffee filter into the house.

Jerrod testified that his father occasionally gave him pseudoephedrine pills necessary for cooking more drugs, and Bob Castleman expressed concern “for appearance's sake” about a large amount of fertilizer (known to be a meth-cooking precursor) stored on the farm.

FROM METH TO MURDER

The FBI believed that despite Jerrod’s testimony about Bob Castleman’s mild involvement in making meth, there was still plenty of motive for the elder to murder Perkins.

When Perkins was shot dead, Jerrod was still wearing an ankle monitor the night, so authorities knew exactly where he was—and it wasn’t anywhere near his friend’s apartment.

But Bob Castleman’s alibi wasn’t watertight. He was at the dog track in West Memphis with a former girlfriend of Jerrod’s. Phone records show he made his last call from there at 12:14 a.m. His female friend reported seeing him next at 4 a.m.

It is a 2-hour drive from West Memphis to Perkins’ apartment if you never stop and push the speed limit.

Some say Bob Castleman would never have been able to make the drive quickly enough to return by 4 a.m. Nonetheless, someone in a wig and trench coat—which were never recovered—was seen entering Perkins’ apartment around 2 a.m.

In a strange twist, Bob Castleman was never formally charged with murder in the death of Perkins. His federal trial judge allowed testimony about Perkins' murder as evidence, however, to show that Bob Castleman’s state of mind: he would never have shot a witness if he wasn’t guilty of the drug charges.

Bob Castleman was the prime suspect because he owned a gun that shot the same type of bullets found in Perkins’ body, Jerrod testified he did it, and his dog-track alibi was weak.

Bob Castleman was convicted of federal drug charges and sentenced to 40-years in prison.

Long before he spiraled into a life of crime, Randolph County native Bob Castleman liked to help people and he was never shy about announcing it. After his conviction, he stated he hoped he could find some way to use the rest of his life for good.

He’s 74 now, locked up a maximum-security penitentiary in Kentucky, with a release date of August 8, 2047.

Become a Front Page Detective

Sign up to receive breaking

Front Page Detectives

news and exclusive investigations.