They were convicted and behind bars. But were let out to commit more crimes. How did it happen?

The story of Mary Vincent is well known among true crime followers. She survived a brutal ordeal after being picked up off a Berkeley, California, street. Her killer drove a van and she didn’t know him, but 15-year-old Vincent was tired after a long day and believed the older man to be harmless.

Once inside the vehicle, the man began to drive off-course. Vincent was taken aback but not unduly alarmed. Mostly, she just wanted to rest. The driver was 50-year-old Lawrence Singleton, a sailor, and he had no intention of taking Vincent where she thought she was going.

He steered his van well out of town and exited from I-5 to the side of a dark road. Singleton knocked Vincent unconscious with a sledgehammer, then raped her repeatedly throughout the night. He unsheathed a hatchet and chopped off both her arms at the elbow, dragging her body down into a culvert and wedging her unconscious form inside a concrete pipe. He believed she would die of her wounds, and he drove off before dawn.

Singleton was arrested in Sparks, Nevada, on Oct. 9, 1978, less than two weeks after he attacked Vincent.

Vincent did not die. She later told her story in a harrowing episode of I Survived. Nearly as horrifying as her ordeal at the hands of Singleton was the justice handed out to him.

Vincent's story has been told far too often. A man convicted multiple times being released from prison only to commit more heinous crimes. Sometimes they are released for political reasons, sometimes it's because of the way laws are written.

But, their latest victims might be alive today if the suspects were kept behind bars with stiffer sentences.

MORE TIME TODAY

Vincent stumbled out of the culvert. She was found early the next morning walking along the road, nude, holding her arms up to keep the blood from flowing and the muscles from falling off. The first car that saw her drove off, too horrified to act, but the second kindly pulled over and drove her to a nearby hospital. She received medical treatment that morning and went on to receive two prosthetic arms.

At Singleton’s trial, Vincent was the key witness.

Her testimony helped convict him, but for his crimes — rape, kidnapping and attempted murder — the maximum sentence was 14 years with the possibility of parole. The judge noted he wished he could put Singleton behind bars forever.

The light sentence was compounded when, based on good behavior, Singleton was released on parole after serving slightly more than eight years. His notoriety made it impossible for parole life in California, however. Contra Costa County rejected him first, then one town after another told him no. Having no place to go in the state, he was offered a trailer on the grounds of San Quentin Prison, where he stayed until April 1988.

Singleton moved to Florida after authorities stopped supervising his whereabouts. In 1990, he was arrested in his new state for petty theft. In 1997, at the age of 70, he murdered Roxanne Hays, a 31-year-old mother of three who made her living as a sex worker.

He was convicted of first-degree murder and sent to death row, where he died four years later of natural causes.

Singleton was known to have a deep-seated hatred of women. Many thought he should have been supervised indefinitely, at the very least, and forced to register as a sex offender. Although sentencing laws have improved, especially for rape, more recent cases of heinous crimes reveal to some that the American justice system hasn’t patched up all its cracks.

THE POSTER CHILD: WILLIE HORTON

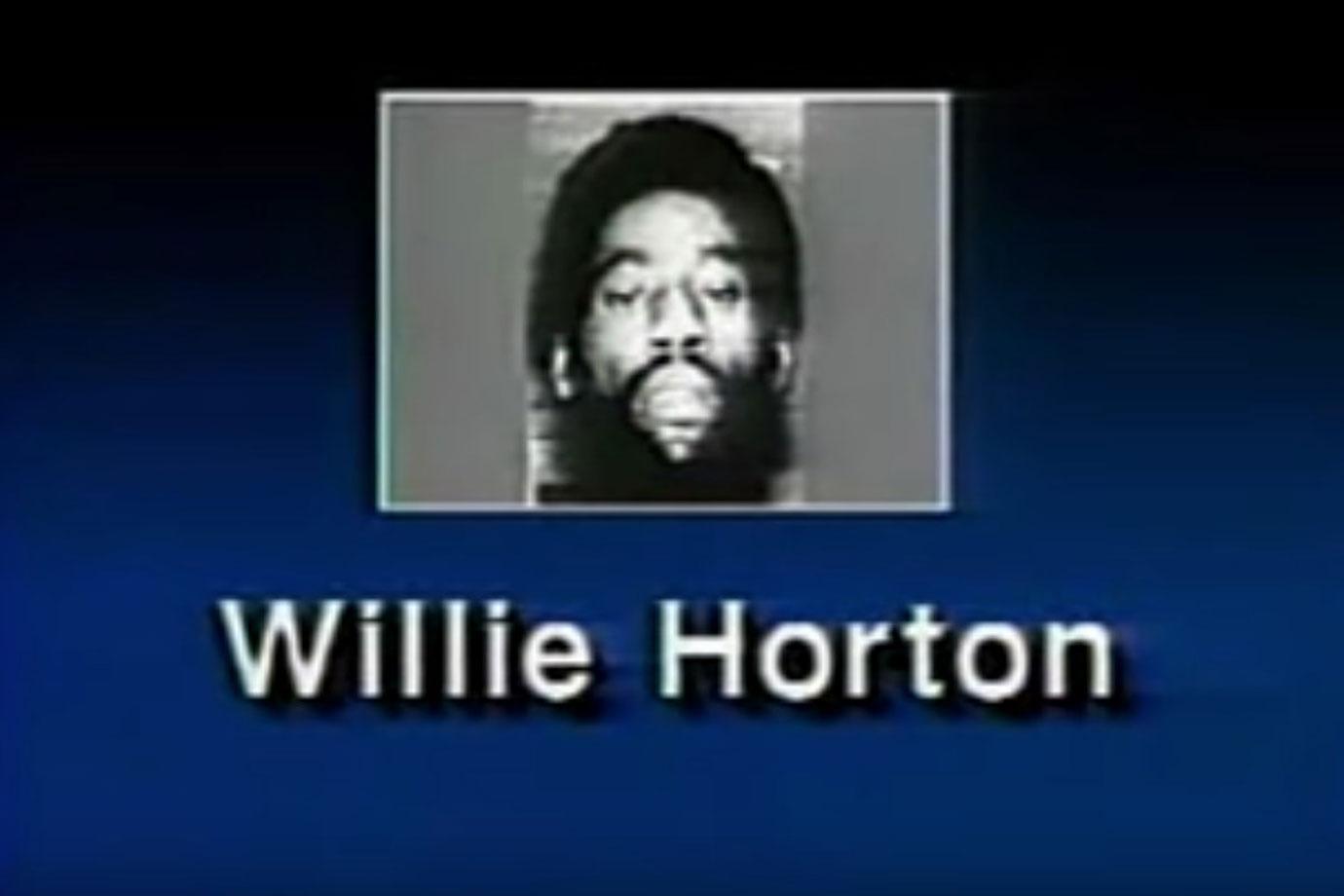

Another situation of a person being released then committing more crimes is a famous case involving a presidential election.

The early release of Willie Horton became a hot-button issue in the 1988 presidential election. Lee Atwater, President George H.W. Bush’s attack dog campaign manager, pushed a narrative about how Michael Dukakis, Bush’s opponent and governor of Massachusetts, released a mad-dog killer into society.

According to the story, it was a law passed by Dukakis that got Horton out of prison.

The reality is more complicated. A series of decisions and reversals by lawmakers made it possible for murderers to access a program created to help non-violent offenders reintegrate into society.

Horton was arrested for first-degree murder in 1974. He was convicted of the brutal slaying of a 17-year-old Joseph Fournier, who had the terrible misfortune of showing up to work that day for his job as a gas station attendant. Horton and two men mugged him. Fournier gave up all the cash, but they stabbed him 19 times and stuffed his body into a trash can. He was unable to free himself and died from blood loss.

Horton was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. He was transported to Northeastern Correctional Center to serve the rest of his life in lockup.

The state inmate furlough program was born in 1972 and signed into law by a Republican governor. It excluded first-degree murders from receiving furloughs. In 1973, the State Supreme Court reversed this exception, but the state legislature sensibly passed a law to ensure first-degree murderers would never receive furloughs.

In stepped Dukakis to veto the legislation. In a classic political compromise, Dukakis supported furloughs because the alternative legislation essentially gutted furloughs on a large scale. He supported a law that would allow any class of convicts to get a furlough — even prisoners serving life sentences without parole.

Horton was still serving his life sentence. He became eligible for weekend furlough on June 6, 1986. Horton left Northeastern and never came back. On April 3, 1987, he showed up in Oxon Hill, Maryland, and broke into the home of Angela and Clifford Barnes.

He assaulted the couple, pistol-whipping Clifford, then binding him and stabbing him. He raped Angela twice. Horton stole their vehicle. The Prince George’s Police Department pursued him, capturing him after a shootout. The judge sentenced Horton, now infamous due to presidential politics, to 85 years behind bars.

Horton now claims he was a victim of a smear campaign. Most states today have furlough programs, but at the time of the Horton debacle, only Massachusetts and South Carolina allowed inmates serving life sentences to take a holiday from prison.

Clifford Barnes, who survived Horton’s attack, has been an outspoken opponent of furloughs, what he calls not a question of race or bipartisan politics but a “common sense issue.”

POLITICS OF A PRISONER IN ARKANSAS

In Arkansas, there was no law on the books to keep the Governor from influencing the parole board when Wayne DuMond, a convicted rapist, was serving out his life sentence.

DuMond had multiple prior arrests. At the age of 22, he was living in Oklahoma and was arrested with two other men for beating a man to death with a claw hammer.

DuMond testified against his accomplices and was not charged with a crime.

A little over a year later, he lived in Tacoma, Washington, where he assaulted a teenaged girl in the parking lot of a shopping center. He was charged with second-degree assault and received a five-year deferred sentence of probation, accompanied by mandatory drug counseling.

Three years after that DuMond, was brought up on rape charges, this time in Arkansas. He’d moved to the tiny town of DeWitt, less than an hour west of the Mississippi River. The rape charges were dropped after he agreed to attend more counseling.

In 1984, he raped another teenager. But this time, in the town of Forrest City, he messed with the wrong victim. Her father was a prominent member of the business community, owning a funeral home. The victim, Ashley Stevens, was also a third cousin to then-Gov. Bill Clinton.

A right-wing smear campaign began, alleging DuMond was framed by Bill Clinton, even though Clinton recused himself from any involvement in the case.

Despite politics, Dumond was convicted and sentenced to life plus 20 years.

But politics reared their ugly form again when the next governor, Mike Huckabee, secured early release for this career criminal.

A convoluted series of events made it possible for DuMond to go from a life sentence to less than 15 years. First came clemency from the acting-Gov. Jim Guy Tucker, in 1992. Tucker’s decision to reduce the sentence to 39 years with the possibility of parole was based on evidence that didn’t get introduced during DuMond’s trial.

The decision made it possible for DuMond to go before the parole board.

On Aug. 29, 1996, the parole board denied parole in a 4-to-1 vote. Less than two weeks later, they voted 5-0 not to commute or pardon DuMond.

Ten days after these two decisions, Huckabee announced he intended to commute DuMond’s sentence to time served. His constituents, the citizens of Arkansas, were not in favor.

On Oct. 31, 1996, Huckabee met in a closed session with the five-member parole board, a group of appointed citizens. No notes exist from this meeting, despite Arkansas state law and the Freedom of Information Act requiring such sessions to have a public record.

Huckabee and DuMond were members of the same evangelical church. It is believed that church members convinced Huckabee that DuMond deserved mercy. Despite the pleas of Stevens, who met face-to-face with the governor pleading to keep DuMond behind bars, Huckabee decided early parole was a good idea.

The Governor also relied heavily on what he’d read about DuMond in The New York Post.

DuMond was released in October 1999. He’d served 14 years in Arkansas for forcible rape and kidnapping, as a habitual offender. As a condition of his release, the parole board stipulated he must leave the state of Arkansas.

The twice-convicted rapist moved to Missouri in 1999, married a member of his church, and on Sept. 20, 2000, was charged with the rape and murder of Carol Sue Shields. He was convicted in 2003. A day before his arrest for Shield’s murder, he murdered a pregnant woman named Sara Andrasek.

DuMond died in prison of natural causes in 2005. The mother of Shields participated in a documentary that went viral on December 13, 2007. She looked straight at the camera and put the whole story of DuMond and Huckabee into perspective.

"If not for Mike Huckabee, Wayne DuMond would've been in prison, and Carol Sue would've been with us this year for Christmas,” she said.

Become a Front Page Detective

Sign up to receive breaking

Front Page Detectives

news and exclusive investigations.