How DNA Helped Catch a Serial Killer for the First Time Over Three Decades Ago

Without DNA, a vicious killer would have continued randomly killing strangers across the state of Virginia. He attacked people in the state capital of Richmond and in Arlington County, just south of the border with Washington, D.C. He raped six women before murdering them by strangulation, but the crimes were not immediately connected.

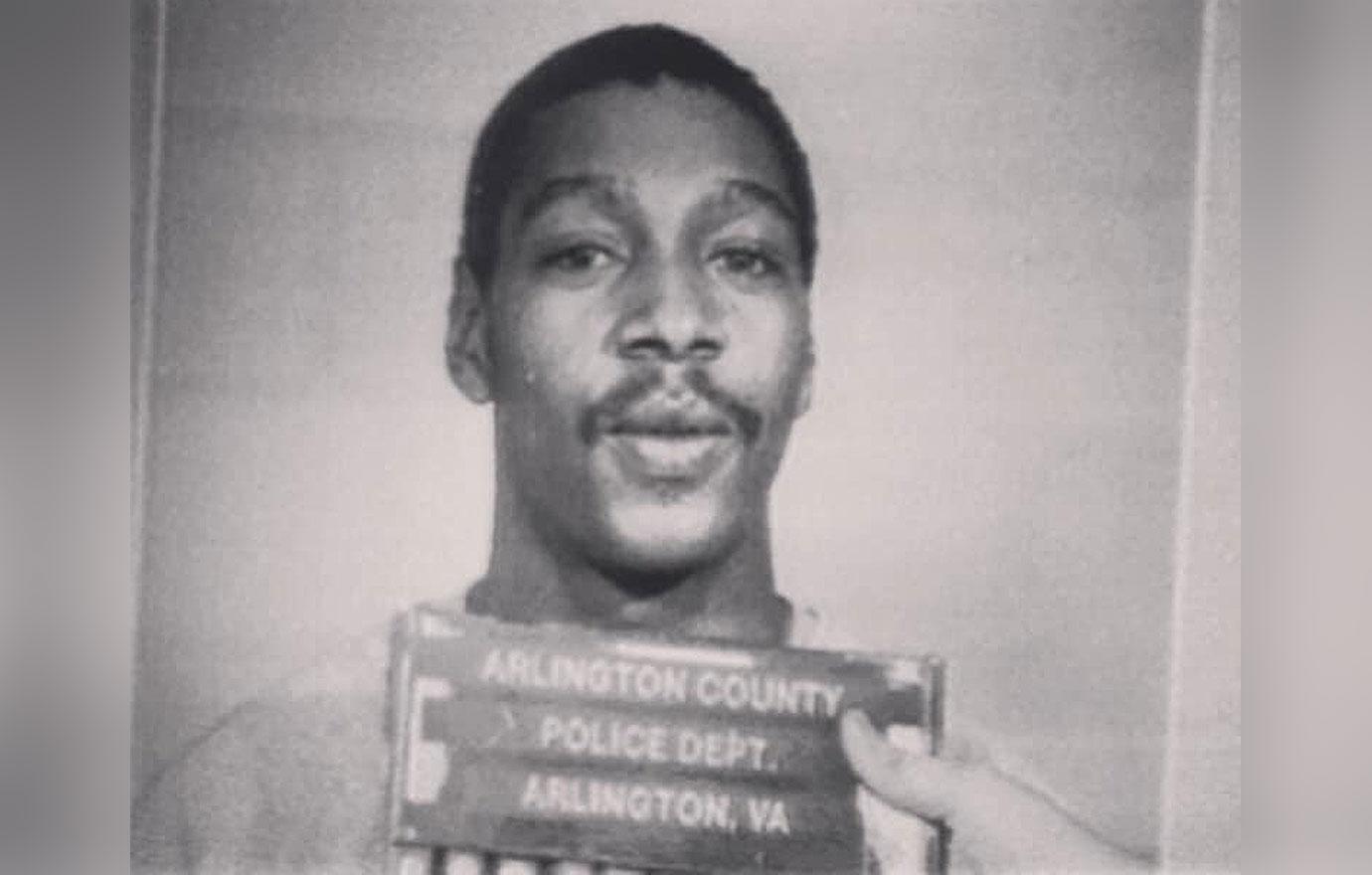

Between 1984 and 1987, Timothy Wilson Spencer, who got the name "the Southside Slayer," made his home in Richmond, Virginia. His modus operandi varied enough to make police wonder if a copycat killer was terrorizing the state capital.

In 1985, authorities arrested and convicted the wrong man for one of the murders. David Vasquez, who was intellectually challenged and confessed under interrogation, spent four years in prison before he was exonerated with DNA evidence.

Spencer's conviction was the first case in Virginia's history to employ DNA fingerprinting to positively ID a perpetrator.

The technology that is commonplace in today's criminal investigations was cutting edge then and helped bring him to justice.

Vasquez was exonerated for the 1984 murder and Spencer received the death penalty. His attorneys appealed to the bitter end, but ultimately the evidence of his DNA left at the crime scene showed chances were more than 1 in 700 million that the rapist and killer was anyone but him.

A NEW TOOL

In the 1980s, most Americans were entirely unfamiliar with DNA as a tool for crime-solving. DNA profiling was first developed only five years before Spencer’s conviction and first used in the summer of 1987 in the case of British rapist and murderer Colin Pitchfork.

Pitchfork was identified after a female employee of the local bakery overheard one of her male colleagues chatting to co-workers at the pub. The man regaled them with the tale of how he’d helped Pitchfork out by taking a DNA test in Pitchfork’s place. She reported what she heard to authorities, who had been meticulously combing the village to collect DNA from every last man after two 15-year-old girls were murdered.

A British genetics researcher in the U.K. developed the first extraction methods, but several months passed before the cutting-edge DNA extraction and testing potential reached American shores.

In the early days of DNA testing, it took six to eight weeks to conduct full DNA sequencing to produce a “fingerprint” or profile.

According to Frontline, another Virginia rapist, Tommie Lee Andrews, was the first American to be convicted based on DNA, for a crime he committed in February 1987.

Spencer, who was only 26 years old when he was captured, was a more virulent criminal. His victims were cut down in the prime of life, and he selected them opportunistically and randomly in Richmond’s once safe neighborhoods. Worse, his behavior was escalating.

THE RICHMOND CRIMES

In January 1984, lawyer Carolyn Hamm, 32, was raped and strangled to death in Arlington, Virginia. She was found hanging in the entryway to her garage. Hamm lived alone and police immediately suspected a stranger. Almost four years later, in December 1987, a second woman who lived near Hamm was murdered similarly.

Professional writer Susan Tucker, 44, was found in her apartment, bound and strangled to death. She, too, had been raped and she lived alone.

The two crimes, although years apart, were connected by the lead detective Joe Horgas, working for the Arlington Police Department. When he arrived at the crime scene at Tucker’s apartment, he was struck by the similarities to the Hamm case and wasted no time in interviewing the man convicted of Hamm’s murder, Vasquez.

Although Vasquez wanted out of jail, he had nothing to offer. Horgas doubted he murdered Hamm and began reviewing the case, according to an interview with Arlington Magazine.

Detective Horgas uncovered nine related crimes that happened in the same area, between 1983 and 1984. His efforts were detailed in media reports and books such as “Stalking Justice: The Dramatic True Story of the Detective Who First Used DNA to Catch a Serial Killer.” All victims, who were raped, described a black man wearing a mask, estimating their attacker to be in his 20s. All the women were raped in their homes, and the rapist usually broke in through a first-floor window.

In September and October of 1983, Horgas learned of three murders fitting the same profile, but they occurred in Richmond, 100 miles south.

The crimes in Richmond were occurring on the right side of the tracks, too: home invasions with women found raped and strangled. The first was Debbie Davis, an accounts clerk. Two weeks later, doctor Susan Hellams was found strangled to death in her home when her husband returned from work.

The last homicide victim was a minor, high-school freshman Debbie Cho who was bound and had her mouth taped. The intruder raped and murdered the 15-year-old while her brother and parents slept in adjacent rooms of the family apartment.

The city of Richmond was on full alert, but justice remained elusive.

A TALE OF TWO VIRGINIA CITIES

While Horgas interviewed the surviving victims of the mysterious masked rapist, his counterpart in Richmond was working on a new investigative technique. Detective Glenn Ray Williams of the Richmond Police Department sent semen samples collected from three crime scenes to a private laboratory in New York called Lifecodes Corp.

Williams thought the three murders were connected and contacted the FBI for help.

Meanwhile, Horgas started working with the FBI to get a profile of the killer and rapist in his town. The information agents gave helped him narrow down the possibilities because they characterized the perp as an individual who would only stop if he were dead or in prison. Horgas began looking through files of past arrests on his beat while racking his brain for repeat burglary offenders who were the right age and race.

The Richmond police had a different experience with the FBI, who offered the opinion they were dealing with a serial killer, but he was likely a white man. FBI profilers drew this conclusion based on the victim’s white race and an erroneous belief that most serial killers are caucasian.

From the outset, Richmond authorities were searching for a white man who burglarized and raped but had graduated to murder.

Horgas in Arlington took a different tack.

He learned an incredible amount of detail after interviewing nine rape victims. He was intimately familiar with the neighborhood where the murders took place, having arrested an array of characters over the years. He spent time sitting in his car on the streets where the murders had taken place, mulling over the likely offenders.

He hoped some detail eventually would come back, maybe even a name.

Williams, meanwhile, was trying to bust Spencer because he, too, suspected the man was connected with the murders.

Richmond police put a tracking device on Spencer’s vehicle. Williams told Richmond’s Style Weekly he often watched Spencer crawl under his car, trying to find the tracker, but he never did. Spencer could have been brought in for parole violation, but after two weeks of watching him not commit rape or murder, Williams was told by his boss to pull the plug on the surveillance operation.

Right around the time the name “Timmy” popped into Horgas’s head, the New York lab had completed DNA profiles for three murders committed in Richmond. If Horgas could find a likely suspect, he knew he’d be able to compare DNA from the suspect with the victims. He thought the man he remembered as Timmy was a good bet, then the last name surfaced.

Horgas and his partner searched records for Timothy Spencer’s arrests and imprisonments. They noted when Spencer was incarcerated and when he was free. They felt a small victory when the math added up: he was free during every single rape or murder in Arlington and Richmond.

THE TAKEDOWN

The suspect fit, but the Arlington prosecutor wanted to make sure to go the extra mile for a clean conviction. District Attorney Helen Fahey was at the murder scene of one of the rape victims, a professional woman like herself, living alone. She was determined to find justice for all the women and get the killer off the streets of northern Virginia before he could do more damage.

Fahey was reluctant to use a simple arrest warrant and decided instead to convene a grand jury. The indictment also listed an address: Spencer was living in Richmond. Detectives from both police forces arrested him after the grand jury handed down an indictment based on existing evidence.

Horgas obtained a voluntary blood sample from Spencer when they got him into custody. The Arlington detective flew to New York to submit the sample to Lifecodes Corporation and learned he’d be waiting six weeks, according to Arlington Magazine.

Horgas obtained a voluntary blood sample from Spencer when they got him into custody. The Arlington detective flew to New York to submit the sample to Lifecodes Corporation and learned he’d be waiting six weeks, according to Arlington Magazine.

He was richly rewarded when Spencer’s DNA matched the sample found on Tucker, Hellams and Davis.

Spencer went to trial first in Arlington in July 1988. After six days of listening to the evidence, the jury found Spencer guilty of rape, burglary and capital murder. In January, he faced a trial for the murder of Hellams and received a second death sentence.

Horgas, with help from Fahey, worked next to release a man they now knew to be innocent — Vasquez.

THE DNA THAT PUT HIM AWAY

The U.S .Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals detailed the evidence used to convict Spencer in an appeal decided September 16, 1993:

Semen stains were found on the victim’s bedclothes. The presence of spermatozoa also was found when rectal and vaginal swabs of the victim were taken. In addition, when the victim’s pubic hair was combed, two hairs were recovered that did not belong to the victim….The two hairs later were determined through forensic analysis to be ‘consistent with’ Spencer’s underarm hair…

The appeal noted that the chances of another black individual having the same DNA profile were 1 in 705,000.

Spencer made several appeals, claiming inadequate counsel and improper admittance of the use of statistical probability in reaching the guilty verdict. Just before his execution, the court denied an appeal to re-test the DNA evidence, according to the New York Times.

The Southside Strangler, 32-years-old, was put to death by electrocution on April 28, 1994, in Greensville Correctional Center, just outside Richmond.

One witness commented in a post that Spencer walked under his own power to the chair, “Old Sparky,” not a feat every condemned man could do. After two jolts of lethal electricity, the Commonwealth of Virginia carried out the best justice it could provide for Spencer.

Become a Front Page Detective

Sign up to receive breaking

Front Page Detectives

news and exclusive investigations.