'There is a family that wants an answer': How one lab uses DNA to help cops solve cold cases

Las Vegas police recently named a suspect in a 1979 killing. Police in Texas identified a teen raped and murdered in 1980 as a Minnesota missing girl. A 1989 homicide victim in Alaska got a name after more than 30 years.

All of those cases shared a common trait — they were cold cases that stumped investigators for decades. They were also all recently cracked, thanks to the work of Othram Labs.

“We don’t solve cases, but we generate investigative leads,” Othram Founder and CEO David Mittelman told FrontPageDetectives, “and those investigative leads sometimes help law enforcement officers solve the case.”

While Mittelman is quick to shift attention away from his lab’s work, police agencies across the country are crediting Othram for helping them solve cases that have long gone cold. It’s now commonplace for an agency to make an announcement of a major development in a case with the help of Othram.

Recently, Mittelman sat down with FrontPageDetective to discuss their work and improvements in DNA technology has helped solve these cold cases.

There are two main areas Othram works, one is cases where help is needed to identify a person, such as a missing person or a homicide victim. The other is to use DNA to develop a potential suspect in a case.

Othram, based in Texas, takes a very small amount of DNA evidence and develops a large genetic profile. That profile is used to identify the person who left the DNA. The information can generate new leads for police, such as through genetic genealogy. That is where investigators take a profile and use it to create a family tree to help them identify the people in the case.

But Mittelman admitted it can be scary to take on cases, and they focus on investigations they know they can help. It’s also scary because every time a piece of DNA is tested, it’s lost forever.

“You don’t want to be the person who burnt the evidence and didn’t get an answer,” Mittelman said.

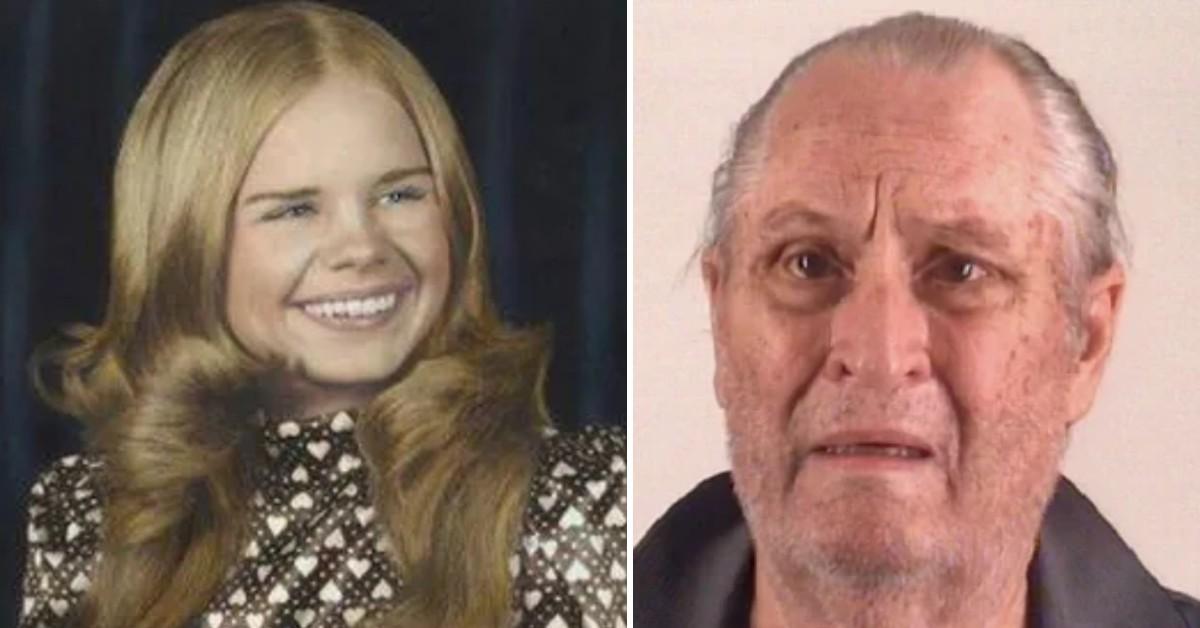

Losing the evidence without an answer is the “ultimate tragedy,” Mittelman said. When they help solve a case, it’s very exciting, and he used the recent example of the Carla Walker investigation. Walker was kidnapped in 1974 in Texas and found dead in a ditch. Her case went cold until Othram stepped in to help.

There were three families destroyed by the crime, the victim, the suspect’s and the victim’s boyfriend, who was identified as a possible suspect, Mittelman said. At a recent court hearing the three families embraced and seeing the hearing was remarkable.

“It’s magical to see that,” he added.

Carla Walker's case was cold until DNA identified Glen Samuel McCurley as a suspect

In the past, law enforcement relied on a national database to connect DNA to suspect. But people were only put in the system after a situation such as being arrested. So many people weren’t included, including homicide victims that were unlikely criminals before their deaths, Mittelman said.

There is about a 1 percent chance that someone can be matched using the national database, Mittelman said.

That is where his lab comes in.

“There is more than catching a bad guy or naming someone that wasn’t known…there is a family that wants an answer,” Mittelman said.

Typically, it takes Othram about 12 weeks to identify the DNA profile once they receive a piece of evidence, Mittelman said. The machines used to run the analysis have a fixed cost and there is a cost-benefit that comes with how often to run the machines, Mittelman said.

The technology for DNA testing is rapidly improving and Mittelman noted they recently took on a case that they had to pass handling in 2019.

While there are many unsolved cases, Mittelman said the bottleneck comes from agencies not knowing the testing exists and informing officials how to use grant funding to pay for the tests.

“I think this kind of testing is very cost-effective if you consider the cost of these investigations,” he said.

Mittelman recalled a recent case where Othram not only helped identify a homicide victim but then helped identify the perpetrator. In that case, it was a twofer for the police agency on its investment.

“They were able to put a name to the person, let the family know what happened to her and then they found the person responsible,” he said.

It was then Mittelman returned to talking to cases they have helped solve. They often come with huge announcements and press gatherings. That is something he would like to see eliminated. Mittelman said he wants the testing to become the norm to help solve cases when other leads run dry.

“I think at some point it just becomes an ordinary thing,” Mittelman said, “and honestly, I think the future we feel embarrassed if you didn’t use the technique.”

Become a Front Page Detective

Sign up to receive breaking

Front Page Detectives

news and exclusive investigations.