Beer, Bullets & Bloodshed: How the Mob Conquered America

On January 16, 1920, the 18th Amendment went into effect. Prohibition, a nationwide constitutional ban on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages, had arrived. Booze was illegal – and America was changed forever.

So convinced were legislative do-gooders that alcohol was at the root of all crime, some towns actually sold their jails, thinking they would no longer be of use. But in fact, they should have built more.

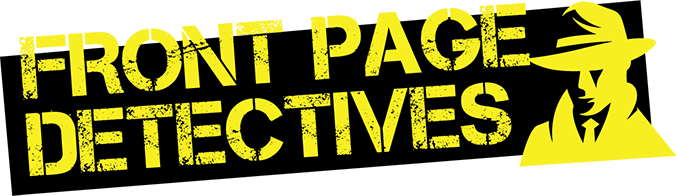

NYC Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach, right, watches agents pour liquor into a sewer following a prohibition raid, circa 1921.

Racketeers took over during America’s “noble experiment,” which lasted until 1933, and served up an ocean of booze to a still-thirsty nation. With people still desperate to get their hands on alcohol, bootlegger operations selling unregulated liquor became the norm.

Untold millions poured into the coffers of Mafia families, Jewish gangs, Irish mobs and other outlaws who became the beer barons of the Roaring Twenties.

Some 30,000 speakeasies – so named because you had to whisper a password to get in – opened for business in the big cities, and even the tiniest towns.

Incredibly, then-President Warren Harding had an illegal liquor stash in the White House. Another hilarious indication that Prohibition was doomed to fail occurred during a bootlegging case in Los Angeles: the jurors drank the evidence. The 12 thirsty men argued they’d simply been sampling the seized stash to determine whether or not it contained alcohol, which they decided it did. The case was tossed.

President Harding (center) - along with Governors and Cabinet officers - wanted to "tighten up" the liquor situation but he kept a secret stash pf booze at the White House.

In Chicago, Mafia strongman Al Capone and rival Irish mobster Bugs Moran got the beer and liquor trucks rolling, adding bootlegging to their gambling, theft and prostitution enterprises.

In Detroit, the murderous Purple Gang, mostly Jewish thugs associated with Capone, smuggled in whiskey from Canada.

Crime lord Arnold Rothstein oversaw rumrunners who brought in boatloads of liquor for the New York speakeasies. His protégés included future Mafia kingpin Lucky Luciano and Luciano’s good friend and partner, powerful gambling lord Meyer Lansky.

In Atlantic City, defiant – and corrupt – political boss Enoch “Nucky” Johnson openly declared his New Jersey seaside resort a watering place for the parched. “We have whiskey, wine, women, song and slot machines. The people want them,” proclaimed Johnson, whose city shoreline was a major drop-off point for illegal liquor coming from overseas.

Al Capone, left, and Jack 'Legs' Diamond, right, made a mint during Prohibition.

Across the country, mob killers whose names would become infamous turned to bootlegging. Handsome Johnny Roselli helped Hollywood’s star enjoy a drink. Public Enemy No. 1, New York’s Dutch Schultz, warred with rivals Jack “Legs" Diamond and Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll over booze distribution. Suave Bugsy Siegel got his start with bootleg booze, and would later make Las Vegas a Mob town.

In Cincinnati, attorney George Remus, believed to be the inspiration for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, was dubbed “King of the Bootleggers,” growing so wealthy he once threw a party where he gave every male guest a diamond watch and each of their wives a new car.

In Tampa, Florida, the city’s numerous inlets and coves became havens for smugglers bringing liquor in from Cuba and the Bahamas.

One of the rum runners of the night circa 1924.

Even corrupt cops – and there were many – got in the action. A Seattle police lieutenant, Roy Olmstead, became “King of the Puget Sound,” using a band of bootleggers to smuggle liquor in from Canada. It earned him more in one week than he made in 20 years as a cop.

Instead of winning a moral crusade against booze, Prohibition spawned immorality. Particularly damning was the lack of enforcement, which led to the rise of the Mob. Its members, like Capone, used bribery, intimidation and murder to stay in business and wipe out the competition.

Prohibition saw some 5,000 lives taken in bootleg-related mayhem among rival gangs. Nearly 800 gangsters died on the streets of Chicago alone, the most notable violence occurring on St. Valentine’s Day in 1929, when seven men associated with Bugs Moran’s gang were lined up against a garage wall and machine-gunned to death by hit men acting on Capone’s orders.

The Saint Valentine's Day massacre in Chicago prompted mob bosses around the country to gather for the very first time.

The brutality so shocked the nation that even the gangsters got nervous. So, three months after the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, they arranged a sit-down in Atlantic City to try and find a way to stop killing one another and continue making a lot of money.

Desperate to end the bloodshed that was hurting business, mobsters from all over America gathered in Atlantic City in 1929. It was the first attempt to create a nationwide crime syndicate.

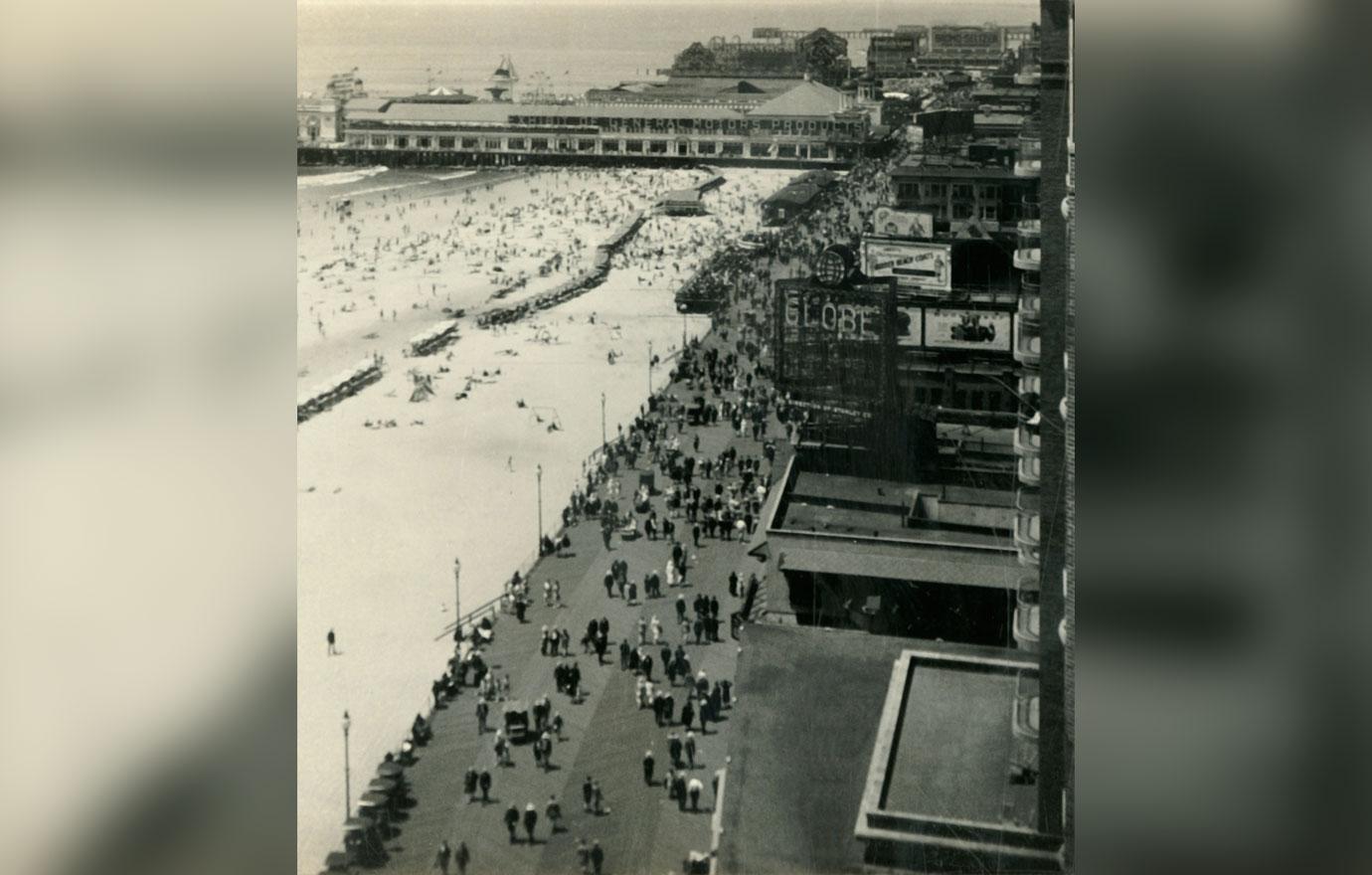

They came from all over. Al Capone was there, even posing for photos on the city’s boardwalk. Meyer Lansky, a newlywed, brought his bride, Anna, and got the Presidential Suite at the Ritz Hotel. He was the one who called for the sit-down. His friend and partner, Lucky Luciano, came along, as did Mafia leaders Frank Costello, Vito Genovese and Albert Anastasia. Dutch Schultz and Bugsy Siegel also joined the historic get-together, the first-ever attempt to form an organized national crime syndicate.

The Atlantic City Conference drew shady characters including Alphonse "Scarface" Capone, third from right, and Enoch "Nucky" Johnson, second from right.

Town boss Enoch Johnson guaranteed no police interference. For the first three days of the gathering, there were constant parties at the hotels as Johnson supplied liquor, food and girls for entertainment. If guests brought wives or girlfriends, Johnson gifted them fur capes.

But then it was down to business.

There were several important items to discuss, including how to handle the constant competition for imported and bootleg liquor profits among the gangs and what to with the liquor business when – as was inevitable – Prohibition ended.

The Atlantic City delegates conducted their more serious business discussions privately, in conference rooms atop the Ritz and Ambassador hotels. But some talks were held out in the open air, with delegates taking their socks off and rolling up their pants for walks along the beach.

Decisions were made to stop competing with each other, and to try to pool resources to maximize profits and develop a national monopoly in the illegal liquor business.

And once Prohibition ended, the bosses decided, they’d reorganize themselves and their gangs into cooperating organizations, investing in legitimate breweries, distilleries and liquor-importation franchises.

Gangsters gathered in Atlantic City discussed forming a nationwide crime syndicate.

The delegates also held discussions about taking a larger interest in illegal gambling activities such as bookmaking, horse racing and casinos.

The glory days were still ahead for organized crime, they knew, and with their coffers filled with Prohibition profits, the gangsters determined to expand their empires to touch almost every phase of American life.

There was one last decision the men at that Atlantic City Conference made: At some point, the racketeers decided that America’s two most powerful Mafia bosses, Salvatore Maranzano and Joe Masseria – neither of whom was invited to the gathering – would have to go.

Maranzano and Masseria were considered “Mustache Petes” – old timers unwilling to deal with gangsters who weren’t Italian, unwilling to change.

Their lives would soon come to a violent, savage end.

Become a Front Page Detective

Sign up to receive breaking

Front Page Detectives

news and exclusive investigations.