The Boy on the Milk Carton: Inside the Disappearance and Murder of 11-Year-Old Minnesotan Jacob Wetterling

The 1980s were a new era for Americans. Personal computers had yet to take over every waking moment, but American life was about to change radically for kids. It was the decade when “stranger danger” crept into neighborhoods across the country. Violent crime was no longer a big city phenomenon as the news of child abductions began to show up in the national news.

In 1984, the first milk cartons with photos of missing children appeared on kitchen tables across America.

In 1989, 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling vanished one autumn night while riding his bike home, accompanied by his brother and a friend. They were on their way through familiar territory—their neighborhood. Thinking there was safety in numbers, Jacob’s dad allowed him to make a short trip to the video store.

What happened to Jacob was, and still is, an incredibly rare event. But it is also every parent’s worst fear, an unending nightmare of wishing a single decision could be reversed.

Child abduction by strangers was something few parents had firsthand experience with, especially in tiny towns like St. Joseph, Minnesota. Most children who disappear are kidnapped by family members. Because it is so unusual, law enforcement in the 1980s often assumed the child has decided to leave, especially in the case of older children and teens. Runaways were far more common than abductions.

But the police knew right away that Jacob hadn’t chosen to stray because his two friends saw him get snatched.

THE WETTERLING FAMILY

Wetterling lived in the tiny hamlet St. Joseph in eastern Minnesota, an offshoot of nearby St. Cloud. It was a typical midwestern small town, not far from the Mississippi River, with plenty of room for kids to roam the quiet streets. Wetterling was a middle child in a stable home with two caring parents, Jerry and Patty. His dad ran his own business as a chiropractor. Jacob’s mom was the primary caretaker for the four kids: AmyJacob, Trevor and Carmen.

Their street was peaceful, but it was a short walk or bicycle ride to the nearby convenience store. Although his mom trusted Jacob at age 11, she did not allow her children to ride or be out after dark.

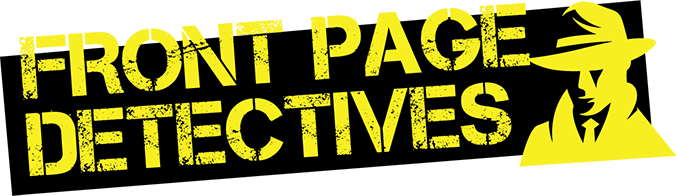

Jacob Wetterling

On October 22, 1989, Wetterling and his brother Trevor were hanging out with their friend Aaron, also 11, while their parents were at a dinner party. It had been a typical fall day, windy and pleasant. By 9 p.m., the wind died down and the temperature dipped to 50 degrees. The boys wanted to rent a video and Jacob called his mom for permission. She said no—it’s after dark.

He decided to give it another shot and then asked his dad, explaining the three of them would wear reflective gear and carry flashlights.

Wetterling got permission from his dad and the three boys rode to the convenience store, rented a movie, and headed back. They shone flashlights because the route lacked streetlights. Out of nowhere, a man surprised them. He was wearing a black mask and wielding a pistol and told the boys to toss their bikes in a nearby ditch.

What happened next sealed Wetterling’s fate. The masked man told them to lie down on their bellies, then asked each child to say his age. Upon hearing Trevor was 10, the man told him to run into the woods “and don’t look back or I’ll shoot.” Next, he asked Aaron and Jacob to show their faces, then he told Aaron to run.

It didn’t take long for Trevor and Aaron to get home and they went to a neighbor, who called their parents right away. They also dialed 911. Within six minutes, a deputy arrived at the scene to find three abandoned bicycles but no sign of Wetterling.

Local authorities contacted the FBI that night. A massive search got underway and attracted plenty of media attention. As the days progressed, the trail went from cool to cold.

EARLY SUSPECTS

Witnesses to the crime were few — two boys. No one saw anyone in the area. The police observed tire tracks and believed the suspect had taken Jacob in his vehicle. By Oct. 25, 1989, the Sheriff had announced law enforcement was certain Jacob had been abducted by a sex offender but also believed the perpetrator had left the area and that his victim was probably dead.

The Wetterling family speaks a memorial service for Jacob Wetterling

The Wetterlings decided to pursue an avenue of garnering as much publicity as possible. The more attention they could get on the case, the better. On Oct. 26, the Wetterling case was profiled on “A Current Affair,” and a $100,000 reward was offered. The next day, the Minnesota governor called in the National Guard.

The FBI assigned 20 agents to the case, but by Nov. 20, the task force had already begun to shrink. The FBI released sketches of the suspect, yet they were unable to make an arrest.

On Dec. 13, a boy named Jared Sheierl told the FBI his story. He lived in the next county, but nine months before Jacob’s abduction he, too, had been sexually assaulted by a strange man who came out of the dark. The 12-year-old was molested but survived. The man who sexually assaulted him in his car and told Jared to run, don’t look back, or he would be shot, according to reports. He showed Jared a gun, and the boy believed him. Before being let go, the man asked him, “Do you recognize me?”

When Jared said no, he was let out of the car.

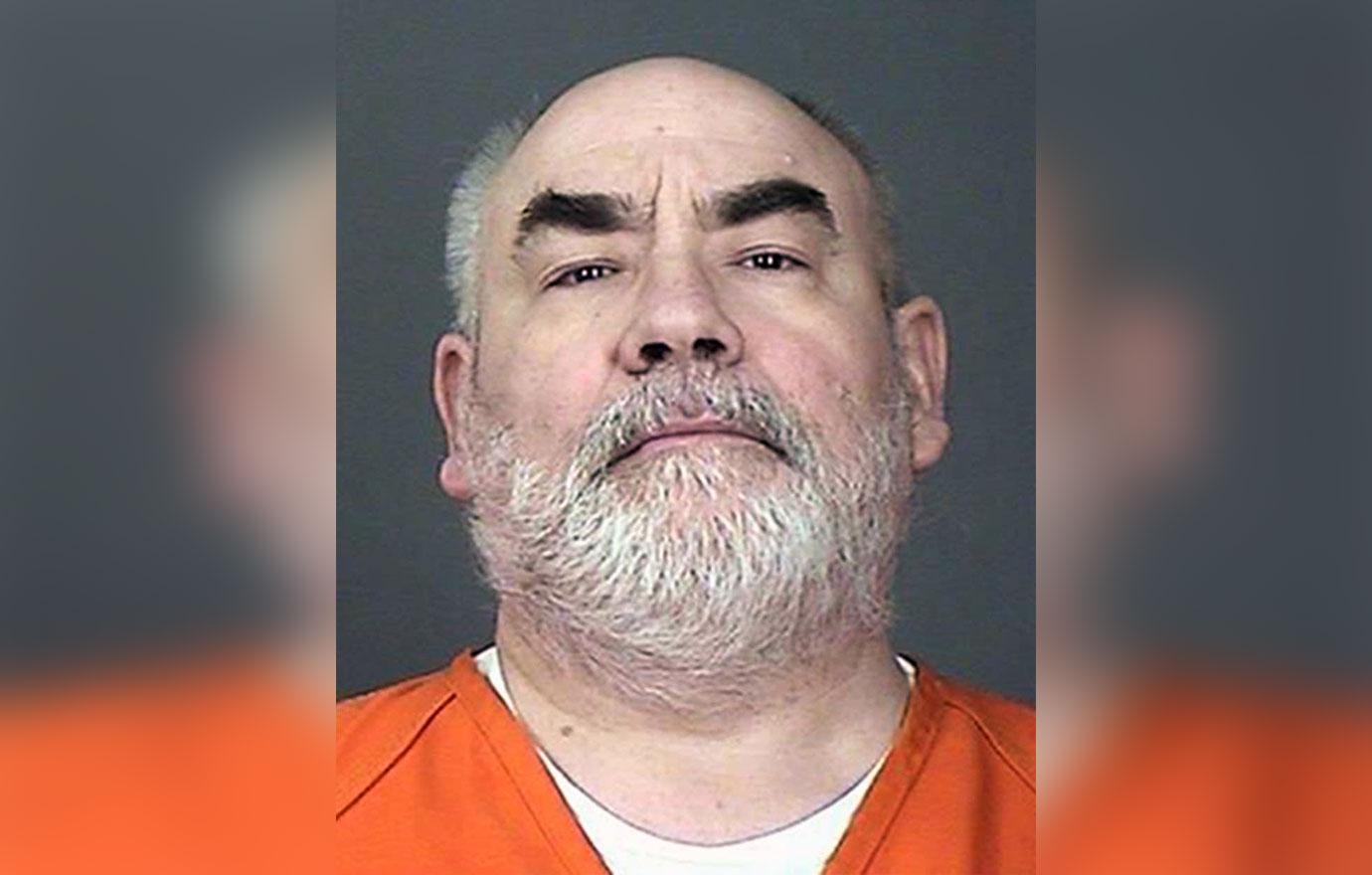

On Dec. 16, based on sketches and other information, the FBI interviewed a man who lived 30 miles from Jacob in the town of Paynesville. The person of interest, Danny Heinrich, denied any involvement. He was reinterviewed again and agreed to give authorities access to his vehicle, prints of his shoes and samples of his body hair. In the next few months, investigators focused on Heinrich but aside from finding child porn at his home, there was no evidence that linked him directly to either Wetterling or Sheierl.

Despite a massive search, the trail to find Wetterling grew cooler. By the end of January 1990, three months into the search, only six FBI were still working full-time on the case.

On Feb. 17, two hundred people gather with Patty and Jerry Wetterling to celebrate what would have been their elder son’s 12th

NO JOB FOR AMATEURS

It is unlikely Jacob’s case would have been solved without the concerted efforts of the FBI and local authorities, but two amateur detectives stepped in to bring it to the finish line years later. The first was Jared, now grown, and the second was a woman named Joy Baker, a blogger and mom who became interested in what happened to Jacob and determined to find answers.

In 2013, Baker began investigating the case. The news media reported a recent search of a farm as a possible grave for Jacob’s remains, which spurred Baker on to get in her car — she lived nearby — and take a firsthand look at the place where Wetterling had gone missing. She then began online sleuthing and eventually found out about Wetterling’s abduction story.

Jared Scheierl, with his girlfriend Stacy Liestman, listens to the Wetterling's attorney Doug Kelley speak to the media outside the U.S. Courthouse

Baker got in touch with Jared, and the two became investigative partners. He badly wanted to find his attacker. One of their first discoveries was the high number of child molestations in the area around the time Jacob disappeared, and all with a similar modus operandi and creepy turn of phrase — run away and don’t look back, or I’ll shoot.

One of the biggest challenges Joy and Jared faced was getting law enforcement to take them, or their efforts, seriously. Neither had any law enforcement credentials and despite telling the Sheriff’s office about multiple similar child molestation incidents, they were often ignored or dismissed.

But they kept at it, talking with Patty Wetterling and documenting every find.

On Aug. 21, 2014, John Walsh’s show “The Hunt” featured the Wetterling case and compared what had happened with Jared’s abduction. This media push influenced authorities, including the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Investigation, to reopen Jacob’s case. In 2015, they re-tested DNA evidence recovered from Jared’s assault and found a match — Heinrich.

'CHESTER THE MOLESTER'

In the community of Paynesville, where Heinrich lived, rumors of frequent child scares and molestations ran rampant in the late 1980s. A man was jumping out of the bushes after dark. Sometimes his face was covered with a mask, sometimes with mud. They called him “Chester the Molester,” and parents kept their kids closer.

When the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Investigation got a DNA match, authorities in Wright County — where Heinrich now lived — issued a warrant to search his one-bedroom home in Annandale. Although unable to prosecute Heinrich for his crime against Jared as the statute of limitations expired, they found a stash of 19 three-ring binders full of child porn, along with other incriminating evidence, during their search.

Danny Heinrich

Deputies also confiscated hours of homemade videotape of neighborhood kids, secretly recorded, going about their daily lives, such as playing sports, delivering newspapers and riding their bikes.

Minnesota filed multiple counts of possession of child pornography against Heinrich, who retained an attorney. At his plea hearing on Sept. 6, 2013, Heinrich confessed in federal district court to kidnapping, sexually assaulting and murdering Wetterling.

At the hearing, an FBI agent showed up along with law enforcement from the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Investigation and an investigator from the Stearn’s County Sheriff’s Office. After discussing changing his plea, Heinrich admitted to owning the pornography, which included up to 150 sexually explicit images of minors, including sadistic acts.

When asked by the prosecutor if Heinrich understood he would be providing a factual account of what happened to Jacob Wetterling on Oct. 22, 1989, Heinrich replied, “Yes.”

When asked if he murdered Wetterling, he replied, “Yes, I did.” Then he went on to recount what happened.

He’d taken Wetterling in his car, driven around until he found a dark field and forced the boy at gunpoint to engage in sexual acts. When Jacob said, “I’m cold,” Heinrich allowed him to get dressed. He then got behind him and shot him twice in the back of the head, according to a report. He buried his body nearby with a backhoe but later realized he’d done a poor job and dug it up reburied it.

Heinrich’s attorneys reached an agreement to only prosecute him for the pornography charges but not for his assault of Sheierl or the murder of Wetterling. The judge imposed the maximum sentence, 20 years, then Heinrich led them to his farm and showed them where he buried Wetterling’s body.

A BRIDGE OF HOPE

The Jacob Wetterling Foundation helped pass a law in 1994 to tighten up requirements for sex offenders in Minnesota to require closer law enforcement monitoring of sex offender release, parole, supervised release and probation. Had the law been in effect when Jacob disappeared, there is a good chance he wouldn’t have been abducted because Heinrich would have already been jailed for earlier molestations.

Patty Wetterling speaks at a memorial service for Jacob Wetterling at Clemens Field House at the College of Saint Benedict on Sept. 25, 2016 in St. Joseph, Minnesota.

Patty Wetterling, who had turned her energies to the foundation and to running for political office, held a press conference once she knew the fate of her son. According to media reports, she told Jacob, “I’m so sorry.”

She thanked Jared and Baker for their thousands of hours of investigation and acknowledged the tireless efforts of law enforcement agencies.

A bridge over the Mississippi River in St. Cloud was funded by the Jacob Wetterling Foundation in 1995. It was completed way ahead of schedule, owing to excellent weather and smooth construction. The ‘Bridge of Hope’ was named by a group of high school students who wanted a permanent memorial to honor Wetterling and a way to remember other missing and murdered children.

Become a Front Page Detective

Sign up to receive breaking

Front Page Detectives

news and exclusive investigations.